| Notes

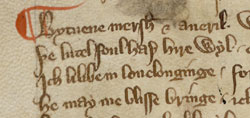

on translating Middle English

introduction

Even if

you're working with the help of a translation, it's important that you

should understand how it relates to (or departs from) the original, so

that you don't make errors in close reading; and not all Middle English

works have been translated, so there are times when you will need to do

your own translations. Even if

you're working with the help of a translation, it's important that you

should understand how it relates to (or departs from) the original, so

that you don't make errors in close reading; and not all Middle English

works have been translated, so there are times when you will need to do

your own translations.

There is currently no satisfactory student's

dictionary of Middle English, and your most useful resources are likely to

be those Middle English readers which include grammatical information and

a glossary (e.g., for early Middle English, Early Middle

English Verse and Prose, ed. J. A. W. Bennett and G.V. Smithers, with

a glossary by Norman Davis (Oxford: Clarendon, 1966, 2nd edn. 1968) or

(where they exist) editions of the individual works with notes and

glossary.

The multi-volume Middle English Dictionary, ed. Hans

Kurath and Sherman M. Kuhn (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan

Press, 1956-2001) is the standard reference work, but can still be usefully

supplemented by the Oxford English Dictionary. Both are now

available on-line by subscription (the former as part of the Middle

English Compendium); University of Southampton on-campus users can

access the Middle English Dictionary at http://ets.umdl.umich.edu/m/mec/

and the OED at http://dictionary.oed.com.

For a

basic introduction to the terminology and concepts used in

dictionaries and grammars of Middle English, see the Introduction

to Traditional Grammar.

top

general advice

The

main pitfall in translating Middle English is not the unfamiliar words but

the words which look the same and mean something different (e.g. nice

means 'foolish', do can mean 'cause to' or 'put'). If your

translation doesn't make sense, look up the words you think you

understood.

It

follows from this that it is often misleading to translate a Middle

English word by the word which has descended from it in Modern English;

and even where the basic sense has remained the same, the overtones may be

different (in particular, a word which was in ordinary colloquial usage in

Middle English may seem archaic to us: e.g. thou). Always

translate sense-for-sense, not word-for-word.

In the same

way, word-order which was normal in the Middle Ages (whether in ordinary

prose or in poetry) can seem unnatural and contorted if carried over to

your translation; you should feel free to modernize it (though make sure

you have understood the syntax of the original first).

Middle

English uses inflexions to indicate grammatical relationships to a greater

degree than Modern English, so it's important that you should be aware of

the implications of different inflexional forms. In particular, make sure

that you can recognize the different forms of the personal pronouns and

the basic verb-endings, both of which can vary from dialect to dialect in

Middle English (see below). You will need a knowledge of both, for

instance, to recognize impersonal verbs (often without a preliminary 'it'

or 'there'): e.g. him liketh doesn't mean 'he likes' but 'it

pleases him', me thinketh not 'I think' but 'it seems to me'.

top

varieties of

Middle English: dialects and spelling

For most of the Middle English period (c. 1100-1500) there was no

national standard written language of the kind we have now, with a single

set of grammatical forms and a fixed spelling.

dialects

Not only

vocabulary but grammatical forms may vary from dialect to dialect. In

particular, you should look out for different pronoun-forms and

verb-inflexions.

a) pronoun-forms:

During the Middle Ages, they/their/them forms of the third person

plural pronoun (derived from Old Norse) move southwards to replace the

older Southern he/here/hem forms (derived from Old English). They

is the first form to move south, followed by their; Chaucer in the

late fourteenth century has they/here/hem for 'they/their/them',

Caxton in the late fifteenth century they/their/hem. One reason why

the Northern forms were ultimately successful is that they got rid of the

ambiguity of early Middle English he (which could mean 'he',

'their', or even in some dialects 'she') and hir(e), her(e) (which

could mean either 'her' or 'their'); you will need to watch out for this.

b) verb-inflexions:

These vary both from north to south, and with the passage of time. In the

fourteenth century there were three main patterns:

present tense:

Northern: I love(s), thou loves, he/she loves, we/you/they love

Midlands: I love, thou lovest, he/she loveth, we (etc.) loven

Southern: I love, thou lovest, he/she loveth, we (etc.) loveth

participles:

Northern pres. pple. lovand; Southern loving

Northern past pple (strong verbs) drive(n); Southern ydrive.

spelling

Be prepared for spelling-variation even within the same text. Reading

aloud sometimes helps (Middle English spelling is roughly phonetic, though

not always systematically).

If you are using a glossary or a dictionary, it's always advisable to read

the introductory notes on alphabetisation and cross-referencing first, as

words may not be listed in the place you expect to find them. Note

particularly:

---both u and v can represent either a vowel or a consonant:

so vnto = 'unto', haue = 'have'. V is usual at the

beginning of words, u elsewhere; so vuel = uvel 'evil'.

---y and i represent the same vowel-sounds (not different

ones, as in Old English). Y is often used where we would use i: so

lyue 'live'.

top

special

characters

Middle English inherited a number of special characters from Old English,

supplementing the characters of the standard Latin alphabet; some editors

replace them by their modern equivalent, but not all, and you should be

able to recognize them if they occur:

The

runic letter 'thorn' is

an equivalent for the modern digraph 'th'; its upper-case form is a larger

version of its lower-case form. The

runic letter 'thorn' is

an equivalent for the modern digraph 'th'; its upper-case form is a larger

version of its lower-case form.

The

letter 'eth',

a modified form of the letter 'd', can also be used as an equivalent for 'th';

it has separate lower-case and upper-case forms. The

letter 'eth',

a modified form of the letter 'd', can also be used as an equivalent for 'th';

it has separate lower-case and upper-case forms.

The

letter 'yogh', originally a form of the letter g used in

Anglo-Saxon MSS, was specialized in the Middle English period to represent

a variety of sounds: The

letter 'yogh', originally a form of the letter g used in

Anglo-Saxon MSS, was specialized in the Middle English period to represent

a variety of sounds:

1. the sound of MnE y consonant: 3ow 'you', e3e

'eye'.

2. the sounds represented (though we no longer pronounce them) by MnE gh:

ny3t 'night' (pronounced as in German Ich), no3t

'nought' (pronounced as in Scottish loch).

3. (rarely) the sound represented by MnE z.

The upper-case form is a larger version of the lower-case form.

The

runic letter 'wyn'

represents w. Not usually reproduced by editors these days, but

you may come across it in manuscripts. Be careful not to confuse it with p

(wyn has a more tapered bowl, and a descender curving to the left)

or with thorn (which has an ascender rising above the body of the

letter). The upper-case form is a larger version of the lower-case form. The

runic letter 'wyn'

represents w. Not usually reproduced by editors these days, but

you may come across it in manuscripts. Be careful not to confuse it with p

(wyn has a more tapered bowl, and a descender curving to the left)

or with thorn (which has an ascender rising above the body of the

letter). The upper-case form is a larger version of the lower-case form.

transcribing

special characters

'Thorn', 'eth', and 'yogh' can be accessed through the 'Symbol' function under

'Insert' on the Microsoft Word toolbar (be careful that you've got the

right symbol in all cases, and that you distinguish between the

upper-case and lower-case forms correctly). If you don't have access to

the special characters for any reason, it's OK to transcribe 'thorn' and

'eth' as 'th', and 'wyn' as w; 'yogh', however is more difficult, as it

has several different values. The simplest expedient is probably to

transcribe it as the numeral '3'; but this loses the distinction between

upper and lower case, so make sure you use the proper character for

serious academic work. Don't in any case try drawing the characters by

hand in your typescript---this looks messy, and encourages errors.

home | contents

| search | top

|